“Anyway, Here’s Modest Mouse”

It’s okay, you don't have to watch the video. Really.

It features a 24 year old me (please don’t do the math, just rest-assured I stopped aging at 45 and it’s been going great) trying to sell a friend’s Sock Monkey and then casually introducing another set of friends’ band by muttering “Anyway, Here’s Modest Mouse.”

Twenty five years ago I was a lot skinnier, beardless and apparently sounded different? It’s surreal to watch now, honestly.

I remember that skinny kid with a red hat and a James Taylor shirt (at an indie rock festival? okay?) but I don’t really remember it as me.

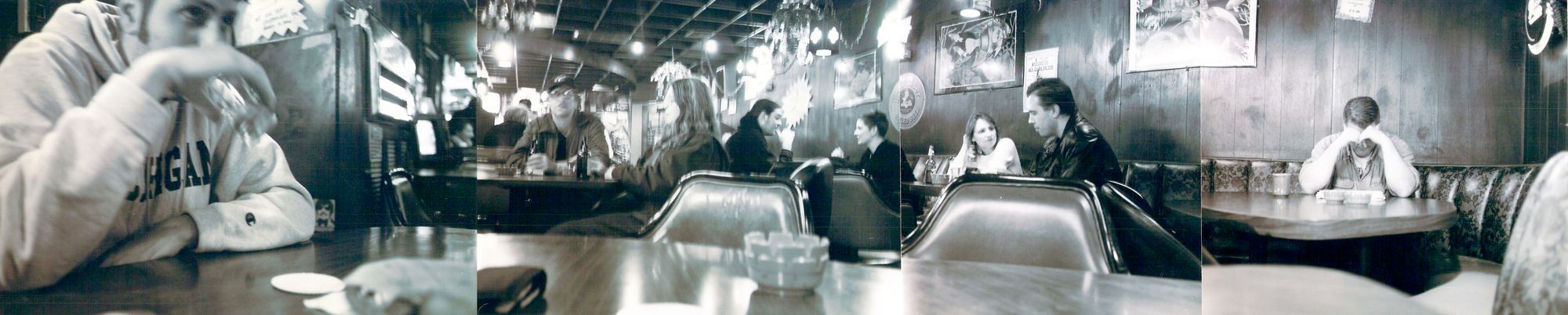

That kid was always running around Olympia doing something; doing album covers for bands, duplicating CD-Rs at night for labels (I was one of the few folks in town who had one, since they still cost over $1,200 at the time), selling tickets at the Washington Center, still working for Housing at the college, helping run the film society day-to-day and, somehow, impossibly, now in retrospect, drinking at least half a dozen whiskey sours at the Reef each and every night.

The latter of which means I did do stuff I regret, sure, but also, it means I don’t remember the whole time as clearly as I maybe could have if things were different.

I remember the “Anyway, Here’s Modest Mouse” part, mostly because it ended up on the record we put out, but trying to sell Rose’s sock monkey? I do not remember that.

It wasn’t until Ryan Baldoz, who now runs Glacial Pace, but whom I’ll always remember first as the relatively quiet and low-key older brother of the girl my friend with only one working kidney was dating at the time, joking said in reply to my “Oh, if you use it, keep in the ‘Anyway, Here’s Modest Mouse’” part, “Should I keep in the Sock Monkey stuff, too?”

Watching it now, I get why I would do such a thing (sell a sock monkey on stage in front of a few thousand people); Tina and Star were running a booth for Catch Of The Day upstairs in the mezzanine of the theater. I worked with Tina at K Records and knew Star from around town. CotD was a mail-order catalog/zine and the spiritual predecessor to the company Aaron and I would start two years later, buyolympia. It was the last day of the festival and they wanted people to check it out who hadn’t yet, to try and clear stuff out. You never want to be left with a ton of merch on the last day when you run an event.

So of course, I’d announce it and try to sell a sock monkey. That’s what you do. It’s what I did.

That’s what the whole community did back then, support each other; give shout outs, help where you could and just feel lucky that we were all getting by, getting to put on shows and have people show up.

I love that people showed up.

Yo-yo was, for me, the embodiment of all that.

I wasn’t part of the planning for the first yo-yo a gogo, the multi-day music-and-more take over of the theater, that was all Michelle and Pat Maley and Kento. I appeared in ‘94 mostly as a thing you got for free for renting the Capitol Theater.

Need someone to sell tickets? I’ll do it.

Need someone to unclog the toilet? Gross, but sure.

Need someone backstage wrangling volunteers? I’m loud, I can do it.

Give me a job, please, I’m a working dog that really, really likes and needs a job to do.

The Capitol Theater was an institution, run by the scrappy-but-super-loveable Olympia Film Society, but in the winter of 1991, I didn’t know that. I was a freshman at Evergreen and put up an 8th annual Olympia Film Festival poster on my wall because I thought it looked cool—or, more likely being the young, naïve Boston-area transplant I was at the time time, maybe thought it would make me look cool?

It wasn’t until a year or so later that I actually got involved, a friend telling me “you know you can get in for free if you volunteer, and they’re having projectionist training this weekend.“ A projectionist in a movie theater? That was, honestly, my 80s childhood dream. The friend bailed the last minute, as folks in Olympia at the time had a penchant for doing, but I showed up.

I met the Film Society’s then technical-director and jack-of-all-trades Jeff Bartone, did the training with a handful of other misfits and started projecting that Sunday evening — a black and white feature, that I actually hadn’t even heard of, Eraserhead. I was, from that point on, there every Sunday evening for the next ten years or so. I participated more and more in everything the theater and the film society had going on; eventually designing every weekly program and film festival guide, being president and introducing over 400 films under the crowd-given-monkier of “Mr. OFS.” I loved it.

I loved that building, knowing and learning every inch of it. Climbing high up in the rafters, three stories above the stage to fix things. Spending a weekend with Jeff pressure-washing and cleaning a river of pigeon poop out of the marquee where they nested. And in a weird way, I loved being the one that had to tearfully announce on one Sunday evening why the power had gone out and the film wouldn’t be shown that evening — that a young tagger had climbed up on the power pole next to the building to get his tag slightly higher than other taggers, and was electrocuted.

The Theater, as we called it, was both a second home and a first best friend. Always there for you with a movie or a $5 backstage show when you needed it most.

I ended up living in the theater that first week of Yoyo a go-go in 1994 (not literally, my apartment was just three blocks away), but was there from morning to night — often the one unlocking the doors in the morning and chaining them closed at 3am.

At the end of the festival Michelle and Pat asked to talk to me, and for a second I thought I was in trouble for something (did I step on someone’s toes?) but no, they gave me an envelope with some money in it, thanked me and asked me to help with the next one, “officially.”

Feeling recognized like that, it makes me tear up thinking about it.

Most of the lessons I’ve always tried to impart on my oldest kid come from that time; a) show up for folks doing interesting stuff, b) see if there’s anything you can do to help, c) try and be as nice as you can to everyone you meet and d) do it because you really want to.

Rent was cheaper back then. Heck, everything was cheaper. Those half-dozen Whiskey Sours? They were a buck each during happy hour.

We use to call it the Five Dollar Happy Hour, because you could get 4 drinks and 4 songs on the jukebox for $5.

But things not being as expensive as today? I think that gave me the freedom to do a lot of that stuff not for money, but for love.

I've been thinking (or trying to, the best I can remember) a lot about life twenty five years ago lately. The things that happened outside of the happy hours, mostly.

Multiple friends touring and sometimes playing songs from records they made over 20 years ago can do that to you.

Bikini Kill, The Mountain Goats, Unwound, Sleater-Kinney, Negativland, and, of course, Modest Mouse.

I just read on wikipedia that The Lonesome Crowded West “is now popularly considered to be one of the defining albums of mid-1990s indie rock.”

It’s weird to have “designed” the cover for any sort of “defining” album, much less one that speaks so assuredly and confidently to a certain time and place.

Was I a graphic designer back then? I’m not sure. I’m not now.

Much like showing up to the theater to sell tickets or serve concessions, I was there. I had a Mac and a SCSI scanner and the rough know-how. I got better the more I did.

Was it design? Back then it was really more of “he’s good with computers” and knows about color separations and taking things to press. I had cut my teeth laying out the school newspaper by hand, so if someone needed help with an album cover or a flyer or film festival program, I volunteered to do it. Happy to help. I loved that stuff.

What is designing an album cover, anyway?

They were Isaac’s fantastic photos—honestly I feel like he never got enough credit for how good of a photographer he was (still is, probably) — I didn’t make the fonts, though did try and pick ones that weren’t in wide use at the time “I really like these slanted letter Os for this,” I remember saying to Isaac as I sat atop a pillow on a worn out $79 office depot task chair, the pillow with a Sesame Street pillowcase that I had since I was a kid, my left leg folded under my butt.

I still sit in that weird way, 25 years later.

But yeah, I picked some fonts, had an idea for the rounded corner box outlines to make it both pay homage to the showing-the-whole-frame-film-marks-and-all that was in vogue at the time and adding a sense of modernism, and then sat there over two days and pulled it all together. The two of us sitting at my brand new Power Mac 8100AV, back when they were just tall beige boxes and hadn’t colored them or given the mirrored doors or anything.

There was something at the time where printing two LP sleeve separately was cheaper than doing a gatefold, or maybe the printer Up Records was using at the time could only do it that way, I’m not sure exactly, but the word from up in high (Chris Takino, RIP) was it was supposed to be two albums covers for this project.

The one “design” thing I really did for that album, that I’m still especially proud of today, is you can stack the albums on top of each other in either order and the spines together spell out modest mouse. Writing the text over two albums means you can order them either way, and the spines will work.

I thought that’d be cool, and still do.

Not sure if anyone else ever noticed or even cared.

The longest part of doing the cover, any cover back then, was typing up the lyrics. Some were scribbled out in Isaac’s notebooks, and others I just typed in as I listened.

It’s funny to get them wrong when the person who wrote them is sitting next to you.

I know I got a few in Trucker’s Atlas wrong; “oh, freight scales, not freight stairs.”

No, I don’t know what freight stairs would be, and to be real, I wasn’t even really aware what freight scales were at the time. Isaac set me straight.

“Working real hard to make internet cash, work your fingers to the bone sitting on your ass,” played off the CD-R I had through the tiny computer speaker, click clacking it straight into quark x-press.

“I love that line,” I said to him, “but do you worry it’ll sound dated in a few years?”

He shrugged and clearly, 25 years later, I was wrong as I could be.

If anything, that line is more true than ever before. Working “hard” on a computer has become more a part of the culture and ethos-of-work than ever before.

I think it’s a line like that which has served to make that album really last, to remain relevant, to help set up the mental picture of the dichotomy that is being both crowded and lonesome at the same time. The New West.

Isaac’s insight into the growth of the West, his observation of where we all are were and are as a country, “I didn’t move to the city, the city moved to me,” is lasting and profound.

And it’s a fantastic rock song.

They are going on tour and they’re gonna play that whole album, soup to nuts.

I’ve gone to shows like this before; The Breeders doing Last Splash was an amazing high and Wolf Parade doing Apologies to Queen Mary made me feel a decade younger.

With the pandemic and a little baby now, I’m not sure I’m gonna go to this one. Right now I feel almost too old for the Crystal Ballroom, I’m just still not ready for strangers in my face on a bouncing floor or some bro loudly singing Cowboy Dan next to me (thinking, perhaps they’re the mythical, iconoclast cowboy of the song—they are not). Maybe I never will be again.

Eric isn’t gonna join them on this tour, so it won’t have his signature bass, and I’m sure it should still sound good, but for me not the same. Eric’s warmth and heart always resonated so personally. His smile and nods, I think I might miss it too much.

Don’t get me wrong, I’ve seen them Post-Eric several times and they’re fantastic. It’s not a knock on the music or anyone new, it’s just different. I couldn’t bring myself to see a post-Deal Pixies, either, if they just did Doolittle. These aren’t hard and fast rules, just what feels right to me at the time (for example, I’m still gonna see Unwound without Vern, but I expect myself to cry through a bunch of it).

Jeremy is still on drums and that’s important. The amount of depth those three created in their 20s with just bass, guitar and drums always blew me away. Isaac’s voice has always been the fourth instrument. Tempo, timing, cadence, highs, lows, crashing with a steady backbeat.

I always feel so lucky to have gotten to see them so many times back in the day. To see songs performed from the album before it was an album. To sit backstage in the wings enraptured like a child.

It’s weird to describe music as “real,” because all music is, but those guys, back then, knowing them, it was the most real. I felt it.

I got to stop by Moon Music while they were recording. Got to chat with Scott in between sessions he was engineering. I got to hear vocals solo’d and see tentative track titles written on tape.

It’s one of those things now that seems even more amazing In retrospect.

I kinda want that time, that album, frozen forever — heck, I’d settle for even my own memories being a little more vivid in parts — but I know it can’t be.

I guess that’s why I’m writing any of this down, now, to help me remember it into the future.

And, to thank my friends and people I knew at the time for being so open, for being themselves. Scared and full of bravado. There for the music, there for each other.

We didn’t know any better back then, it’s how we were.

Don’t forget, we’re all counting on you.

Don’t forget, we’re all counting on you.